When did we split from the sacred?

By "we" I mean the "Western", White, Anglo-Saxon, Judeo-Christian peoples. My people, my ancestry.

In my time living close to and learning about Indigenous traditions especially in the Andes of Peru, I came to wonder: where and when was my lineage Indigenous? We are all from somewhere originally, we all were native to someplace at sometime, right? So when did my family lose our Indigeneity?

At first I thought, it was when we left the land, that the physical settling on one piece of land and staying in one place generation after generation was the characteristic of Indigeneity. Which I do not have as my ancestors left their homelands in the 1600s and early 1900s, I grew up as a settler/colonist/invader on Native American lands, and I have moved to several countries none of which match my native ethnic heritage.

But I came to realize that it is not about place itself, it is about mentality. Our relationship to the place. And that was broken long, long before.

When the goddess was murdered.

When divine-nature herself was assassinated by a Male God.

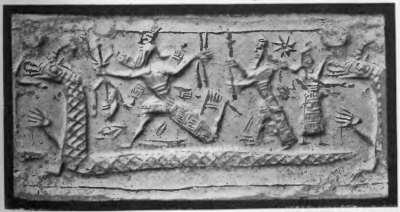

This story is recorded in the Enuma Elish, the Babylonian creation story, around 1750 BCE. The myth tells of the conquest, defeat, and assassination of the mother goddess Tiamat by the male god Marduk.

Image: Marduk killing Tiamut, in form of snake. Seal cylinder.

Source: https://www.sacred-texts.com/ane/blc/img/017.png

We, the Judeo-Christian-Islamic heritage, have inherited this story, as all three religions trace their mythological roots to this story and the earlier Sumerian version. In fact, Baring and Cashford in The Myth of the Goddess (1991) attest that all myths where a god or hero conquers a serpent or dragon can be traced to this story (p. 274). Think of the Garden of Eden, of Catalonia's Sant Jordi, or so many fairy tales adapted into Disney movies. This story is rooted deep in our collective unconsciousness, and yet we do not consciously know what the symbols are.

As Baring and Cashford explain,

this myth constitutes the completion of the process of transfering

sacred principle from the Mother Goddess to Father God, from one who

generates and embodies, who is creation, to one who makes

creation separate from himself: "In this way the essential identity

between creator and creation was broken, and a fundamental dualism was

born from their separation, the dualism that we know as spirit and

nature" (p. 274).

For nearly 4,000 years, Western, patriarchal cultures have told and retold the myth of the death of the goddess, disguised as a snake or dragon. Every time we tell these stories, we witness again the violent murder of the Mother Goddess. We celebrate the hero. We relish in the death of the threatening dragon. And we have inherited the duality of spirit and nature as something inherent, given and eternal. We assume this is the natural way of things, the "right" way. We have been taught to forget what came before.

It is still there - that ancient human memory of the goddess, of nature and spirit as one. For us, it is a memory; for Indigenous people, it is a living concept and practice.

This is the difference.

When this myth took hold thousand of years ago in Babylonia, we split with the sacred. And this Iron Age myth represents the shift in collective consciousness in that time period, in that region: from unity, harmony, balance and fecundity to conquest, war, patriarchy and fear of death. Most unfortunately, this worldview became the dominant one, considered more valued and more valid than that of Indigenous and non-Western peoples.

Poignantly, this story promotes the doctrine of maligning and destroying the feminine - including Mother Nature, an implicit message in force today, with devastating consequences.

Image: The personification of nature in the Andean cosmovision is Pachamama, Mother Earth.

See https://www.ellitoral.com.ar/corrientes/2013-8-1-8-1-0-pachamama-ofrendas-y-danzas-en-honor-a-la-madre-tierra

In a theological sense, this myth represents the shift from believing that nature itself is divine to believing that divinity exists beyond the natural world, in a male god made in human form. This set up the belief that humans could and should control, subdue and have domain over nature, instead of being part of it/Her.

Pinpointing this moment in history, traveling back to this story, understanding it, questioning it, tracing its legacy through Biblical stories and Disney movies, discovering its doctrine in corporate practices and climate policies -- this is crucial to dismantling the dominant exploitative, extractivist, patriarchal, misogynist paradigm that is poisoning creation.

Making space for alternative creation stories from other traditions can also open us up to break from the hegemony of this violent legacy. Learning how Indigenous traditions talk of creation and the relationship between humans and nature can rekindle that memory we have deep inside.

For example, in this short video, Artist Abraham Matias (@abematias) compares different creation stories and asks us to consider, where do we come from? What ancestral wisdom do we wish to unearth?

Repositioning the death of the goddess as what it is -- a myth, a story -- instead of divine truth and natural order, would go a long way in diminishing its monopoly power on our consciousness and mentality.

And perhaps we could finally grieve the death of the goddess and through that grief, bring her back to life.

Comments

Post a Comment