There is a story we tell every year: in the deep midwinter, a virgin mother gives birth to a son-god-king in a stable, marked by a bright star. In this Christian myth, the child who is born is the son of god, god incarnate, who came to the world to save the people from sin, a savior.

The story has such influence on our current society that his supposed birthday literally marks the before and after on the calendar of the history of the world. Even those who do not believe in the doctrine of this story are still familiar with the themes. And for those who believe or not, there are elements of the story that are perhaps unconvincing, that do not quite seem to fit, that feel like they need a leap of faith to believe.

So, where did this story come from? Why do we collectively need to retell it every year? And why was it set now, at the time of winter solstice in the northern hemisphere?

Let's go back 20,000 years...

In the Paleolithic era, from the Pyrenees to Siberia, our cave-dwelling ancestors sculpted forms of women, often naked and pregnant. Thousands of figurines have been found across the region. These sculptures surely had a ritual purpose, and a focus on fertility and regeneration. As Baring and Cashford write in The Myth of the Goddess , "Because the whole of the body is concentrated on the drama of birth, the story that these and many other figures tell is the story of how life comes into being" (p. 8).

|

| Goddess of Laussel, 20,000-18,000 BCE |

The oldest story is the story of how life comes into being. The mystery and drama of birth and life itself.

Mystery and drama are key elements of the Christian myth that we retell today. The Virgin Birth maintains many elements of ancient stories, transformed over time to respond to changes in consciousness and power in society. And the fact that this story has endured over thousands and thousands of years, signifies that something in it speaks deeply to the mystery of who we are and how we came to be as humanity.

Entertaining the thesis of the Sacred Principle (the focus of this blog), I propose that the reason we retell this story over and over, the reason it has endured in some form in the dominant ideology of the Western tradition, is that it encapsulates this ancient, primordial story. And in some way, the goddess herself is speaking through this story, to keep herself and her message alive and in our consciousness, albeit implicitly. Until enough people inquire and uncover the deeper, older meanings: the unity and sacredness of life. A meaning we desperately need to remember if we want to shift our current state of destruction of all creation.

Tracing the story

As an exercise, I will trace the story and symbols of the Virgin Birth from the Paleolithic era to the current Christian myth. The parellels are astounding, and also bring new meaning to a story that has tried to cover up, extinguish and erase the original goddess myth. For this, my primary source is The Myth of the Goddess (Baring and Cashford, 1991). The authors reference Jung, Campbell, Gimbutas, hundreds of authors, original myths and stories from the Bronze age on, and even the Biblical apocryphals as they build their evidence base. In further study I would research all of these sources personally as well as advances since the publication of their tome in 1991, but for the sake of this short piece, I lean on Baring and Cashford primarily.

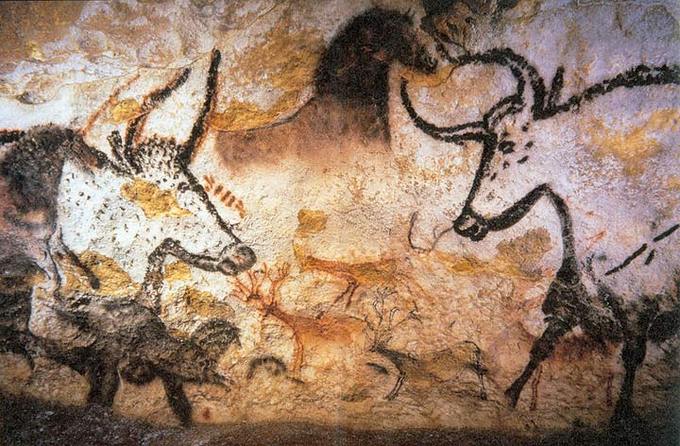

In Paleolithic times, the sacred images of the "Mother Goddess" represented "the life-giving, nourishing and regenerating powers of the universe" (Baring and Cashford, p. 8). People used caves as sites of ritual, where the cave represented the womb. Life and death were a constant cycle, and through it all, the Mother endured, just as the phases of the moon changed but the moon remained. The parallels in images are also startling: from a carving found in around 20,000 BCE to images of the Virgin Mary painted recently, the goddess is often accompanied by a crescent moon. As the authors write, "From the Paleolithic cave sanctuary with the animals pained on the walls to the stable of Bethlehem with the ox and the ass, from the ancient Mother Goddess to the Virgin Mary, there runs an ancient and extraordinary pattern of relationship" (p. 45).

|

| cave painting from Lascaux, France |

In the Neolithic era, this tradition of the "Great Mother" continued as society transitioned from cave-dwellers to farmers. The territory where the imagery has been found ranges from Britain through Old Europe and Anatolia to Syria and the Indus Valley, representing a "cultural unity" in this period (p. 104). The collective consciousness maintained the "original sense of unity...explicitly explored through the myth of the goddess" (p. 47). In this period, the goddess was the creative source of life and rebirth and all of creation, including us, were her children, her epiphany, her manifestation -- and also sacred. In the period between 5th and 4th millennia BCE, the image of the pregnant goddess evolves into images of a dual goddess and the mother with her offspring. These renditions represent "the Great Mother as source and what comes from the source -- the child as the constantly renewed cycle of life" (p. 71). Another evolution between 7th and 6th millennia BCE was the distinction of female and male elements. Where previously, the Great Mother embodied the male and female or was androgynous, now images emerge with male anatomy, sometimes personified as half-man half-animal (often a bull) and sometimes "by the figure of a man portrayed as a god" (p. 74).

The island of Crete represents an area that continued this goddess tradition later in time than mainland regions, due to its protection from invading forces. In this culture, life was a celebration and society was peaceful. In Crete, the story of the child of the goddess continues. Over time, the images evolve from a child appearing with two goddesses, the male aspect as a young son-lover and eventually an adult male god. Notably, in the images the young god is in a position of reverence, service, worship or adoration to the goddess. In myths passed down, the goddess is also a queen and priestess, the god is a king and priest, who unite in a sacred marriage, the union of sun and moon, where the son-lover is then sacrificed ritually to ensure regeneration of Earth in springtime. The god, then, maintains the aspect of renewal like the original manifestation of the Mother Goddess, as an annual or yearly god that is born and dies every year, like the cycle of vegetation -- and like the Christian myths of Christmas and Easter that endure today. The authors posit that "the myth of the goddess reached its culmination here before its gradual decline" (p. 144).

|

| The mythological god Zeus was born on Crete |

The Bronze Age of Sumeria and Egypt represent a marked transition from the original goddess myth. Thanks to the writing that emerged in this period, we have original stories about the beliefs formerly represented through art alone. At the beginning of this period, the Great Mother Goddess is present, as the origin or source, and then becomes many, with siblings and children. The goddess is totality, the whole, the eternal cycle of life and death. The children, deities in mortal form, are a part manifested in life, that is subject to that cyclical process. By the middle of the Bronze Age, the goddess starts to be replaced by the male principle and even father gods in a warrior ethos inherent in the violent, patriarchal Aryan and Semitic cultures invading and conquering the region. New myths emerge of the separation of heaven and earth, where creation is not birthed from the mother goddess but a male god replaces her as the creator. The warrior ethos was based on fragmentation, opposition and separation: light and dark, life and death, male and female, nature and the sacred. This polarity was also infused with judgement: the male was predominant to the female, the light better than the dark... In Sumeria, the one Great Goddess of unity became two opposing forces of good (life) and terrible (death). Finally, legends emerged elevating the son of the goddess, to king with divine status. The focus shifted from the old myth of phases of renewal to "the new myth [where] the hero stands alone against the opposing force, supported by his father in heaven" (p. 174).

In Mesopotamia (Babylonia and Sumeria) in the Bronze Age, the images and stories of the goddess link directly to the Christian Virgin Mary. The goddess Inanna or Ishtar is represented with the crescent moon, a bright star and roses and called in different variations, Queen of Heaven and Earth, Holy Sheperdess and Keeper of the Cow-Byre, shown holding a child, who was called "the Shepherd", "Lord of the Sheepfold", "Lord of the Net" and "Lord of Life" (p. 177). Another Sumerian goddess called "the mother of all living" was symbolized by an inverted U shape, representing "the birthplace, womb, sheepfold or cow-byre from which new life came into being....There is a suggestion that a lying-in place for women to give birth was associated with the temple, housing the sheepfold, cow-byre and granary within its precints" (p. 190). Written myths from the period describe the goddess and her "Faithful Son", a young son-lover, "Lord of the Sheepfold and Cattlestall" (p. 207). The parallels continue as Mesopotamian culture had a direct influence on Hebrew culture.

|

| from Baring and Cashford, p. 193 |

Next came the Iron Age, where a new myth emerges in Babylonia and spreads wide and far: the original mother goddess is murdered by the male god (her great-great grandson), who then makes creation and becomes Father God (see previous post on the split from the sacred, for an in-depth look at this myth and historical moment). This myth becomes the root for Judeo-Christianity. While the Old Testament puts prime focus on Father God, the authors trace veiled references to goddess worship, with parallels both to the original mother goddess and the forthcoming Mary in the New Testament. Both Eve and Sophia or Wisdom are explored as expressions of the goddess myth in the undeniably patriarchal Old Testament. It is telling that, as Baring and Cashford write, "There is no word for goddess in the Hebrew language" (p. 447). The goddess was intentionally demoted, disparaged, and disappeared from the story. But what was lost with her was even more profound: the sense of earth and all creation as living and sacred.

And then we come to the virgin birth of the New Testament. In the Bible, the same archetypal story as previous eras is clear: Jesus, son of god, born of the Great Mother, Mary. Mary is known by many of the names cited from previous myths; even the name "Mary" comes from the Latin for sea, referencing the primordial waters of life, as are previous mother goddesses. This god-son was the manifestation of divinity, but also had to be sacrified to ensure the regeneration of life or as Christians say, to save the world from sin. Even the setting of the birth in the manger harkens back to the Bronze age myth from Mesopotamia of sheepfold and cow-byres. And the star above the stable was the symbol of goddesses in Mesopotamia.

|

| classic Christmas nativity scene |

One important aspect of this story is Mary's virginity. The original meaning of the word virgin means "the source that continually generates itself" (p. 74). In this way, the Paleolithic Mother Goddess was a virgin, as there was no evidence of a differentiated male aspect. But this concept of virginity was very different for Mary, where sexuality is associated with sin. And yet this aspect is crucial to Christian morale: "It is fundamentally Mary's virginity that is the cornerstone of Christian theology, for without it there could be no 'Son of God'" (p. 537). Curiously, the primal aspect of being a mother was set in opposition to virginity, analogous to purity, a patriarchal imposition relevant in the historical context. So virginity went from being a symbolic to a literal trait, but also set Mary up as herself divine -- a goddess -- despite the best intentions of the church fathers. Mary does not fulfill the full embodiment of the virgin mother because of the split of the sacred with humanity: "The feminine principle has not been doctrinally acceptable as a sacred entity for at least 2,000 years, and consequently any union of masculine and feminine principles in the language, image and word of orthodox theology is unthinkable" (p. 554). Nevertheless, she represents the mother figure, the mother of divine creation in the form of Jesus, and a beyond-human woman endowed with divine characteristics.

This birth, imbued with hope, joy and celebration, was and is a ritual at the darkest time of year. Since Paleolithic times, in the northern hemisphere, this season of darkness was a time of waiting for the birth of new life or in the Iron Age mythology, for the light to conquer the darkness. The winter solstice, the shortest day of light and longest night, marks the moment of shift back to increasing light: the return or rebirth of the sun. Specifically, 25 December was winter solstice on the Julian calendar, and winter solstice is symbolically "the birth day of the sun god, the luminous divine child" (p. 561-2). There could also be another element: if springtime was when animals including humans mated, impregnation around spring equinox would result in birth around winter solstice (see the post of Cova Parpalló for more on this).

Understanding the meaning

The story of the virgin birth has been passed down over millennia, symbolic of the rhythm of natural cycles, and imbued with meaning that we have forgotten -- or intentionally has been withheld from us. From the very first story, told through little stone sculptures that our ancestors left near caves, we understand that the feminine principle, pregnancy and birth were sacred, revered and mysterious. The mother goddess was the never-ending source of life, and all her offspring were manifestations or epiphanies of creation. Everything was sacred, whole and connected. The male principle emerges as an element of fertility, also in reverence to the female, mother goddess, as her son, lover, consort and partner in divine unity. When this god takes on protaganism as the creator, he violently murders the goddess and separates nature from divinity. But the goddess does not die: she lives on in symbol and story, and re-emerges as Mary, Mother of God.

In scripture, Mary is barely mentioned, but in art, poetry and icon, "Mary is the unrecognized Mother Goddess of the Christian tradition" (p. 547). According to Baring and Cashford, it was the people who called for and created the deification of Mary, through petitions in church councils and paintings in cathedrals. She has been depicted as mother, daughter and even priestess-wife, with the stars, moon, roses, animals and waters of earlier myths. Catholics fervently pray to and revere Mary in thousands of manifestations across time and culture (Our Virgin of...).

| More than an earthly mother, Mary is depicted as deity in religious art |

What is the meaning of this? Why do we retell this story, of the virgin birth, year after year?

The authors cite Jung's idea of a collective consciousness, saying, "To live fully, we have to reach down and bring back to life the deepest levels of the psyche from which our present consciousness has evolved" (p. 45). That would be, the original story of the mother goddess as the source of the mystery of birth and life.

The goddess never completely disappeared even in patriarchal societies and ideologies because "humanity seems to have need of the image of the divine mother as well as the divine father" . There is "human craving for a divine mother" and a "psychologically determined predisposition to believe in and worship goddesses" (p. 449, citing Patai, The Hebrew Goddess).

The goddess myth persevered because something within us reminded us that the story we were being told was not quite the whole story, not quite the whole truth. As much as the Christian theology tried to silence the goddess, she found ways to survive in the collective unconscious. And now, it is important to remember consciously: "The goddess myth needs to be made known not because it is superior to the god myth, but because it has been lost so long that we have apparently forgotten what it meant" (p. 485).

According to Jung, there is an "inherent self-regulating balance of the collective psyche" , meaning that when one principle is distorted, "the unconscious psyche will, apparently intentionally, compensate for this distortion by insisting on an opposing point of view in order to restore the balance" (p. 554). So the protaganism of Mary in the Christmas story persists as a counter-balance to the male-focused theology of Christianity. The male and female need to come back into balance. But also, the ethos and significance surrounding each: the feminine principle associated with nature, intuition, connection and care, to balance the out-of-control patriarchal masculinity of violence, destruction, separation, polarity and competition wreaking havoc on our earth and our society in modern day.

What next?

There is no going back. There is no inherent superiority of the goddess myth over the god myth, and in fact in many aspects the goddess myth would no longer be relevant in our time and culture. Our consciousness has evolved, our understanding of the world has changed, and our relationship to nature and divinity is different than it was 20,000 years ago.

The story of the virgin birth is timeless and compelling because it captures a shared truth that we feel without having to understand. It sets a scene with archetypal images that evoke meaning we do not even remember we know. It fulfills a need in us to honor, in annual ritual and according to natural rhythms, the great mother and the return of the light after a period of darkness. It is the theatralisation of overcoming fear and darkness, waiting hope and faith, and celebrating joy and love -- universal and timeless experiences.

The specific story of the birth of Christ is also imbued with religious doctrine responding to specific ideology based in historical context. Now we are in a much different historical context then the year Jesus was supposedly born, over 2,000 years ago. So maybe, it is time for a new story, a new myth, that can embody the archetypes and symbols from the time of the caves to now, and also balance the feminine and masculine principles, to tell the story of the sacred principle coming back into union and consciousness.

Who can tell this story?

Comments

Post a Comment